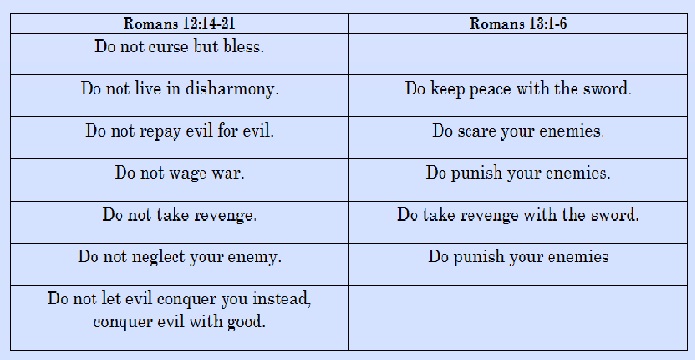

Does the requirement of obedience to the government relieve the believer of individual ethical responsibility? The activist view is most likely erroneous. The apostles recognized that they had to heed God first (Acts 4:19-20; 5:29). There is no question that the believer is expected to obey the government. However, Romans 13 is also clear that the government’s authority is derived from God (13:1, 2, 4, 6). Thus, the believer should pay taxes (13:6). However his subjection is not required when the government expects something that is not legitimately due (13:7). The higher authority is God.

This does not mean that the Christian prevents the state from engaging in war or from defensive preparations which might deter aggressors. The separation of Church and State allows the government that privilege. However, Christians are still bound personally by a higher priority established by a higher authority. God has made each Christian a member of the Body of Christ. The responsibility to fellow believers is abundantly clear in the NT. Numerous commands about love, forbearance, unity, and kindness fill the pages of the NT. How can the Christian violate such commands in the name of patriotism?

In addition, even with qualifications added, the spirit of the Sermon on the Mount and direct statements such as those found in Romans 12 and 13 regarding the treatment of enemies are binding upon Christians. Individual ethical responsibility must enter in if a believer is personally on one side of the gun aiming at another person who is there only because a war has been declared. Thus, in my view, this higher priority bars that kind of participation in war.

Commonly the issue of self-defense is raised against this position, “What would you do if a man was threatening to kill your family?” To move to this personal and emotional plane obscures the issue. “Nonresitance in war and nonresistance in this situation are not necessarily parallel cases.”[1] There is a difference between defending one’s family in this type of situation and planning to take lives in war.

It is wholly illogical to pose this problem as the test for the non-resistance position. In war the situation is known and the movements are all premeditated and planned with precision. Surely the Christian who feels that the Word of God warns him against the show of violence cannot deliberately plan to do the very thing he knows is un-Scriptural.[2]

To permit self-defense when one is personally threatened with violence does not necessarily permit one to join in war and take the lives of “enemies” because they are from another nation. The separation of Church and State and commitment to fellow Christians forbid the latter practice but not the former.

Each Christian must ask, “What is my responsibility? What decision should I make in regard to participation in war?” I can summarize my own view of such responsibility in three statements.

First, it is my responsibility to trust God as my ultimate defense. Some may feel that the noncombatant believer leaves to others the defense of the nation. While I would not deny the responsibility to participate in such defense as far as conscience allows, my ultimate trust differs from that of many of my fellow citizens. My faith is in the sovereign God as the ultimate Defender of me and my family. Even those believers who in clear conscience fully participate in war need to examine their priorities. Perhaps Christians should be as concerned to pray for the security of their nation as they are to guarantee its military defense.

Second, it is my responsibility to serve my government as far as conscience and my commitment to Scripture allows. The separation of Church and State and my citizenship in the heavenly kingdom does not mean that I am to be isolated from the society in which I live. Christians are not to go out of the world (1 Cor 5:9-10) though they are “not of the world” (John 17:15-18). Rather they have been sent into the world (as Jesus’ prayer in John 17 indicates). Non-resistance then should not be passive but rather active as Christ’s commandments are carried out.

Third, it is my responsibility to serve my fellow man. Serving my fellow citizens and my government may well involve going into life-threatening situations knowing that I will not be bearing arms. However, my service may involve binding wounds or serving as a chaplain. Thus, my refusal to take lives in the name of the government is a biblically limited participation not a refusal to participate. I prefer to call this “noncombatant participation” in war.

[1] Hoyt, Then Would My Servants Fight, 85.

[2] Ibid 86.