By Warren Harrington in From the Eye of the Storm, eds., Kaplan, Bove.

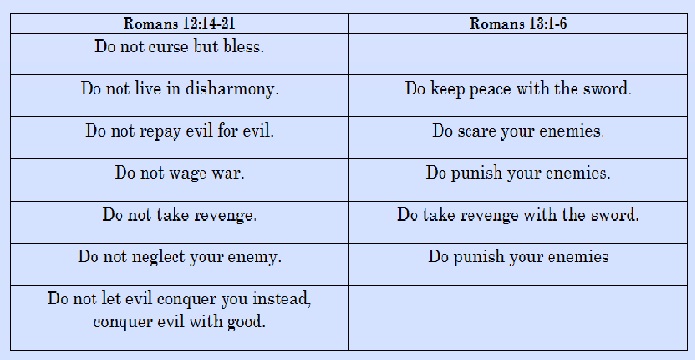

4. Letter to Marcellinus

Marcellinus, Imperial Commissioner at Carthage, wrote Augustine for help in discussions about several topics of the faith with Volusian, a Pagan senator from Carthage. Marcellinus is seeking a letter marked by “that shining splendor of Roman eloquence” (Letter 136:1) for which Augustine is famous. One concern is with the uniqueness of Jesus: how, the Pagans ask, might he differ from magicians such as Apollonius and Apuleius? Another concern is about the proper role of sacrifice, and another about the charge that Jesus’ preaching and doctrine were not adaptable to the customs of the state, especially war. Of particular concern are the teaching about turning the other cheek and the principle, “Render to no one evil for evil” (Rom. 12:17). Volusian and his friends ask, “Who would not wish to return evil, as the law of war allows, to the ravager of a Roman province?” Are these Christians truly loyal supporters of the Emperor and his right to make war?

Augustine wrote the letter to Marcellinus in 412, a year before he began work on The City of God. In it, he argues against a literal reading of the text on turning the cheek and not rendering evil for evil. Instead, he offers a psychological explanation. The text on not rendering evil is to be understood as calling for “refraining from the passion of revenge–in other words, choosing, when one has suffered wrong, to pardon rather than punish the offender, and to forget nothing but the wrongs done to us” (138:9). Thus, use of force without revenge is “not rendering evil for evil.”

These precepts pertain rather to the inward disposition of the heart than to the actions done in the sight of others, requiring us, in inmost heart, to cherish patience along with benevolence, but in the outward action to do that which seems most likely to benefit those whose good we ought to seek (138:11). Thus the teaching does not rule out forceful, even coercive, actions if they have practical value. Punishment is even justified, so long as it is not vengeful.

Augustine next claims that the Christian teachings are in accord with the noblest ideals and performance of Roman tradition. Augustine asks how it was possible that the Republic of Rome was able to grow and prosper, to move from obscurity and poverty to greatness and opulence, if the leading men lived by a code of vengeance. To the contrary, argues Augustine, Rome’s founders and benefactors were men who “when they had suffered wrong, would rather pardon than punish the offender” (138:9). Indeed, turning the cheek was practiced by Rome’s forebears and has practical, persuasive value. Turning the cheek is done, Augustine reminds Marcellinus, “that a wicked man may be overcome by kindness.” One senses here Augustine’s wish to promote Christianity as the official religion.

On the basis of this interpretation of the scriptural teaching, Augustine turns to the conduct of war and calls for an ethic of good intention and benevolent design. If the Commonwealth observes the precepts of the Christian religion, even its wars themselves will not be carried on without benevolent design that, after the resisting nations have been conquered, provision may be more easily made for enjoying in peace the mutual bond of piety and justice (138:14).