War, Peace, and the Christian Tradition

by

Mark Allman

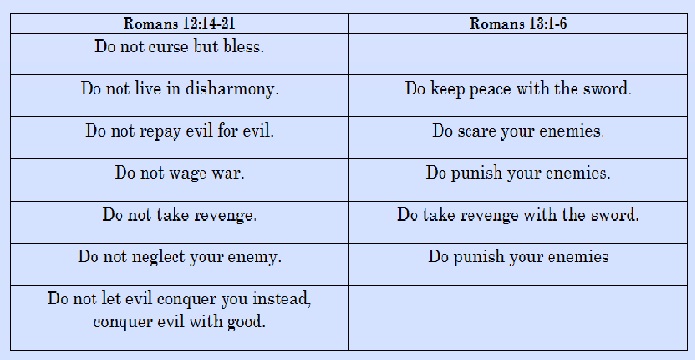

The question of whether Jesus was divine wasn’t settled until 325; the debate over the doctrine of the Trinity and the role of the Holy Spirit wasn’t settled until 381; all of which means that, for the first 350 years of Christianity, there was no uniformity of belief regarding the very nature of God. Interestingly, the early Christians were fairly univocal in their stance toward the use of force and violence, however. For the first three to four centuries of Christianity, pacifism was the norm for Christians. [p 77]

In the early Church, a commitment to pacifism was considered a constitutive or essential element of the Christian faith. So how is it that today most Christians are not pacifists? Tradition holds that after a victory he credited to the Christian God in 312, the Roman Emperor Constantine became a supporter of Christianity, thus reducing persecution by the pagan Roman religion in which the emperor was considered a god. Shortly after, the Edict of Milan permitted Christian worship within the empire. Constantine’s toleration and eventual privileging of Christianity posed serious challenges to the Christian faith. How would a once persecuted minority religion based on the teaching of a first century Jewish rabbi adapt to being the official religion of a world superpower? It is impossible for an extended empire like that of the Romans to rule by a commitment to pacifism. By 416, only Christians could serve in the empire’s military. In little more than one hundred years after Maximilian and Marcellus were beheaded for refusing military service, the Christian stance on the use of force had changed completely. What had happened? [p 83]

Interestingly, Augustine and Ambrose forbade clergy (priests and monks) to participate in military activity because they celebrated Eucharist, which required a ritual purity. Thus we see even in this early slide toward the ethics of empire (that is, an ethic that justifies certain activities in the name of state interests) an uneasiness regarding the use of force. It was something that had to be rationalized. Augustine and Ambrose did not praise the use of force, nor did they fully justify it; instead they reserved it as an instrument of statecraft. [p 85]

Simons and the Anabaptist tradition are challenging and fascinating. In their attempt to return to biblically based Christian faith, they came to the same conclusion reached by early Christians like Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, Maximilian, and Marcellus: the gospel of Jesus Christ requires a commitment to pacifism, and resorting to force is akin to renouncing one’s faith. The Anabaptist tradition and its radical commitment to pacifism survive to this day among the self-identified “peace churches”: Anabaptists (Mennonites, Amish, and Hutterites), the Church of the Brethren, and the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), as well as in a number of other Protestant denominations that have also historically espoused pacifism.